(This post is also available ad-free from my website)

As any family historian knows, you start with yourself and work backwards. Eventually the trail goes cold and you enter the domain of the general historian. Further back and the archaeologists take over.

You don’t expect your named ancestors to be of interest to the archaeologists but that is the situation with Anne McColl.

Anne was one of my wife’s 4th great-grandmothers. Around 1766 Anne was born at Swordlemore on the Ardnamurchan peninsula, the most westerly point of the Scottish mainland.

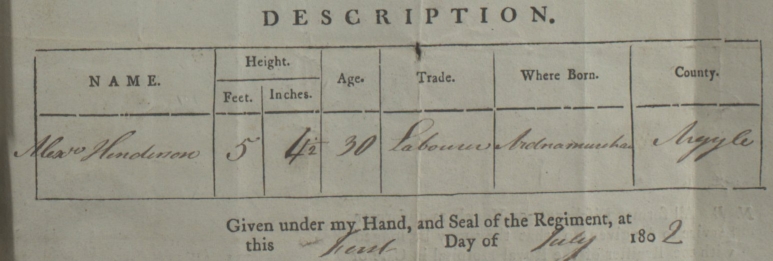

Anne married Alexander Henderson around the time that the First Fleet made landfall in Port Jackson, New South Wales, to initiate European settlement of Australia.

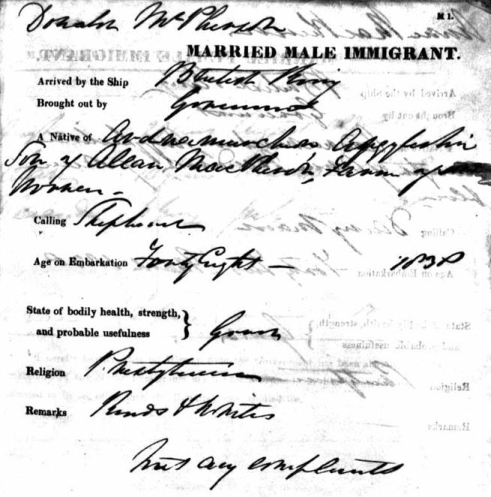

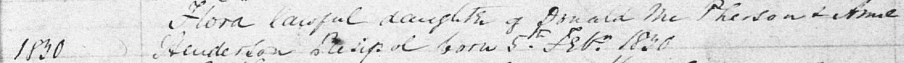

Their daughter Anne Henderson, born about 1789, was to marry Donald McPherson at Kilchoan in Ardnamurchan around 1817. In 1839, Anne and Donald, with their 8 children set sail for Australia – but that’s a story for another post.

Recently I decided to follow up the few clues that I had concerning Anne Henderson’s parents. These comprised names mentioned in immigration papers.

Further clues came from Anne’s death registration from 1865 which gave her birthplace as Kilchoan, Argyllshire, Scotland and her parents as “Alexander Henderson and Ann McCall”. Cut to the chase and we find Anne Henderson, born Anne McColl dead on 27 March 1855 at Portuairk, also on the Ardnamurchan peninsula.

1855 is a significant year for family history research in Scotland as it was in that year that compulsory registration of deaths was introduced. That means that there is a very complete record of the basic facts of Anne’s life.

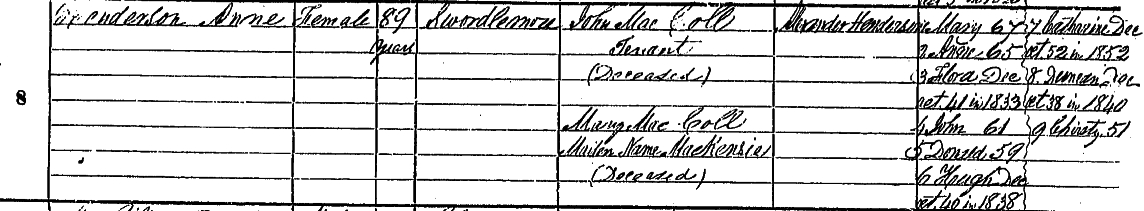

Portion of Anne’s Death Registration

Here are a few facts about Anne derived from the death registration and census information. She was born about 1766 in Swordlemore, the daughter of John MacColl, tenant, and Mary MacKenzie. Married to Alexander Henderson, she had 9 children. In 1841 Alexander and Anne were living with their son Donald and his family at Swordlechorach.

By the time of the 1851 census Alexander had died, and Anne, aged about 85 years, was still living with her son at Swordlechorach.

Coincidentally, 1851 was the year that Thomas Goldie Dickson, acting for the trustee of Sir James M. Riddell’s Ardnamurchan estate, compiled a report on the condition of the estate’s tenants. This includes recommendations as to how they were to be dealt with in relation to their arrears of rent.

Donald Henderson is entry number 114 in this report. It shows that his rent arrears amounted to 33 pounds, 14 shillings and 14 pence, and that his stock (cows, cattle, sheep and a horse) were worth 90 pounds. It describes his situation thus:

“Wife alive, 4 children, oldest 7 years, his mother still living with him. Arrears have risen gradually since 1848 should go to Australia & would have no objections to go.”

In the final column is the recommendation as to how he should be dealt with – “sequestrate” – which means that his assets would be sold up to satisfy his debt to his landlord.

It’s a well documented fact that in 1853 the tenants at Swordlechorach were subjected to “clearance” from their holdings. Houses were pulled down to prevent re-occupation and the families were moved to inferior land at Portuairk and other places. From the facts that Portuairk was where Anne died in 1855, and where her son Donald lived in later years, we can conclude that they were amongst those cleared from their holdings. Donald appears to have chosen his mother over emigration to Australia.

In another post I have given more information about the experiences of the Henderson family during their eviction.

That was the end of that particular story I thought. However in September this year (2015) I became aware of the Ardnamurchan Transitions Project, which is exploring the archaeology of the Ardnamurchan peninsula.

Part of the project’s research has been the excavation of remains of the houses at Swordlechorach.

The final report of these excavations is due soon, so I’m looking forward to seeing what it reveals about the lives of the families of Swordlechorach.

Like to know more about Ardnamurchan? Visit the outstanding A Kilchoan Diary blog.

(Herrmann Family History)